Book Review: Setright’s Morgan

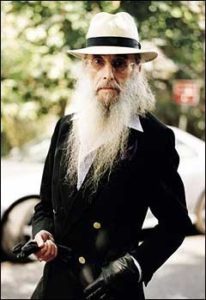

The great LJK Setright is no longer with us, but he left a legacy of the finest motoring writing. In his unfinished autobiography, soon to be published, he recalls the three-wheeler he drove during his National Service:

RAF Sopley was, as I have noted, deep in the countryside. Thus there were occasions – not many, for I enjoyed being in the service – when I needed transport to take me elsewhere.

In due course I found what every young man should experience early in his motoring career; a Morgan three-wheeler. It was the Aero model, dating from 1926, with two-speed transmission involving chains for the final drive, one on each flank of the rear wheel.

The engine was a V-twin JAP, albeit only the soft-tuned water-cooled side-valve job rather than the hot overhead-valve versions sometimes fitted. The body had been modified (sensibly, but not prettily) around the tail by the previous owner, who had also had the wit to scrap the hand-lever throttle control clamped to the steering wheel spoke and substitute an accelerator pedal such as is familiar in cars.

More to the point, much of the machinery was worn out, but since I had only paid £57 10s 0d for the thing I could not really complain…

What had suffered worst was the carburettor, a handsome old brass Brown & Barlow instrument whose needle and surrounding jet had been so abraded by the passing of time and of each other that the delivery of mixture to the engine was decidedly imprecise. There was also dermatitis in the magneto, which made starting doubly problematic…

In due course a new Amal carburettor (with which petrol consumption improved by 85%) and a magneto rebuild cured these troubles, and that little Moggie gave me enormous satisfaction.

It was very strictly an open two-seater, almost a one-and-a-half-seater in the style of those racing cars which had been its contemporaries: the seats were staggered, the passenger’s being slightly further back than the driver’s. This reduced frontal area put the driver nearer the centre-line of the car, the better to see and to steer. The passenger could also put his right arm behind the driver’s shoulder to free more space and, if he could find something to grip, help him to stay in place when cornering, which the low and light Morgan did rather well.

Too well for its own good, perhaps. The front wheel hubs were more like those of a perambulator, or perhaps of a bicycle, than those of a car: with inadequate lateral bracing from the spokes they flexed inordinately, adding their own slip angle to that of the tyres so that the three-wheeler was unexpectedly a natural understeerer.

After a couple of weeks of blissful three-wheel drifts along cursive lanes, spokes began to break. On one afternoon of strong sun, during which the Morgan was parked on a steeply cambered road, several spokes broke in one of the front wheels. On another occasion, as I took a 90-degree left hander in the grounds of RAF Stanmore flat-out in the 36mph bottom gear, the offside wheel simply collapsed, and the Moggie finally grounded itself to a halt on the grass just a few feet from the building which, I learned, housed the RAF Theatrical Wardrobe. I still wonder why the service should need such a thing.

There is something so intrinsically right about a tricycle properly planned – the most vital criterion being that the centre of mass should be as low as feasible. That was certainly true of the low-slung Moggie: when I first took my brother out for a drive he shook his pipe out over the side prior to recharging it with tobacco, felt a slight jar and brought his hand back holding merely the stem, for the bowl had hit the road and shattered!

The Morgan was not to be criticised for this, but rather the design of tobacco pipes. The low-slung design of the vehicle did more than merely make it stable; it enhanced the balance, because the tricycle has its rear roll centre more or less inevitably at road level beneath the rear tyre…

All this prompted a good deal of confidence in driving, so that I could relax on almost any journey and enjoy the physical sensations to which a low, open, lightweight vehicle brings one so close. The surprisingly gentle pobble of the engine out in the open air ahead of the radiator was a steady reassurance; the smell of hot oil weeping from the valve guides, of fresh oil and petrol from the ventilated filler-caps ahead of me on top of the bonnet, were somehow confirmatory that all was working as it should, and were a mere scent carried away by the headwind, not a stink stuck in the cockpit.

In the long dips and swells of the A30’s gradients on a deep winter’s night I could sense in my face the changes in air temperature and calculate whether the road surface was likely to be icy or dry; the rest of me warmed by the air which blew in through the radiator and, heated there, continued into the cockpit to take the chill off the nether Setright. Motoring in open cars really does have a charm all its own, if one is not going too fast.