Monthly Archives: August 2016

Book Review: Setright’s Morgan

The great LJK Setright is no longer with us, but he left a legacy of the finest motoring writing. In his unfinished autobiography, soon to be published, he recalls the three-wheeler he drove during his National Service:

RAF Sopley was, as I have noted, deep in the countryside. Thus there were occasions – not many, for I enjoyed being in the service – when I needed transport to take me elsewhere.

In due course I found what every young man should experience early in his motoring career; a Morgan three-wheeler. It was the Aero model, dating from 1926, with two-speed transmission involving chains for the final drive, one on each flank of the rear wheel.

The engine was a V-twin JAP, albeit only the soft-tuned water-cooled side-valve job rather than the hot overhead-valve versions sometimes fitted. The body had been modified (sensibly, but not prettily) around the tail by the previous owner, who had also had the wit to scrap the hand-lever throttle control clamped to the steering wheel spoke and substitute an accelerator pedal such as is familiar in cars.

More to the point, much of the machinery was worn out, but since I had only paid £57 10s 0d for the thing I could not really complain…

What had suffered worst was the carburettor, a handsome old brass Brown & Barlow instrument whose needle and surrounding jet had been so abraded by the passing of time and of each other that the delivery of mixture to the engine was decidedly imprecise. There was also dermatitis in the magneto, which made starting doubly problematic…

In due course a new Amal carburettor (with which petrol consumption improved by 85%) and a magneto rebuild cured these troubles, and that little Moggie gave me enormous satisfaction.

It was very strictly an open two-seater, almost a one-and-a-half-seater in the style of those racing cars which had been its contemporaries: the seats were staggered, the passenger’s being slightly further back than the driver’s. This reduced frontal area put the driver nearer the centre-line of the car, the better to see and to steer. The passenger could also put his right arm behind the driver’s shoulder to free more space and, if he could find something to grip, help him to stay in place when cornering, which the low and light Morgan did rather well.

Too well for its own good, perhaps. The front wheel hubs were more like those of a perambulator, or perhaps of a bicycle, than those of a car: with inadequate lateral bracing from the spokes they flexed inordinately, adding their own slip angle to that of the tyres so that the three-wheeler was unexpectedly a natural understeerer.

After a couple of weeks of blissful three-wheel drifts along cursive lanes, spokes began to break. On one afternoon of strong sun, during which the Morgan was parked on a steeply cambered road, several spokes broke in one of the front wheels. On another occasion, as I took a 90-degree left hander in the grounds of RAF Stanmore flat-out in the 36mph bottom gear, the offside wheel simply collapsed, and the Moggie finally grounded itself to a halt on the grass just a few feet from the building which, I learned, housed the RAF Theatrical Wardrobe. I still wonder why the service should need such a thing.

There is something so intrinsically right about a tricycle properly planned – the most vital criterion being that the centre of mass should be as low as feasible. That was certainly true of the low-slung Moggie: when I first took my brother out for a drive he shook his pipe out over the side prior to recharging it with tobacco, felt a slight jar and brought his hand back holding merely the stem, for the bowl had hit the road and shattered!

The Morgan was not to be criticised for this, but rather the design of tobacco pipes. The low-slung design of the vehicle did more than merely make it stable; it enhanced the balance, because the tricycle has its rear roll centre more or less inevitably at road level beneath the rear tyre…

All this prompted a good deal of confidence in driving, so that I could relax on almost any journey and enjoy the physical sensations to which a low, open, lightweight vehicle brings one so close. The surprisingly gentle pobble of the engine out in the open air ahead of the radiator was a steady reassurance; the smell of hot oil weeping from the valve guides, of fresh oil and petrol from the ventilated filler-caps ahead of me on top of the bonnet, were somehow confirmatory that all was working as it should, and were a mere scent carried away by the headwind, not a stink stuck in the cockpit.

In the long dips and swells of the A30’s gradients on a deep winter’s night I could sense in my face the changes in air temperature and calculate whether the road surface was likely to be icy or dry; the rest of me warmed by the air which blew in through the radiator and, heated there, continued into the cockpit to take the chill off the nether Setright. Motoring in open cars really does have a charm all its own, if one is not going too fast.

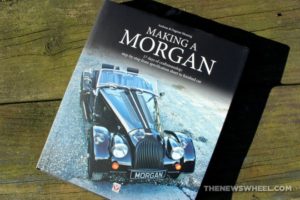

Book Review: Making a Morgan: 17 Days of Craftsmanship: Step-by-Step from Specification Sheet to Finished Car

An inside look at the making of an automotive icon from specification sheet to finished car. https://thenewswheel.com/

The Morgan Motor Company is a David among an industry of Goliaths. England’s last independent, privately-owned automaker has been resistant to the changing production methods and neutered styles of the modern automotive industry–despite being advised to “get with the times.”

This high-end automaker has established a consistent identity for nearly a century as a producer of new, vintage cars that are built by people, not machines. Its lineup of unique, highly-customizable models includes the 3 Wheeler, 4/4, Plus 4, Roadster, Plus 8, and AERO8.

To immortalize the spirit of the Morgan, a husband-and-wife duo have witnessed and chronicled the production of a Morgan Plus 4 at the company’s Malvern factory. Making a Morgan: 17 Days of Craftsmanship captures the inner secrets of Morgan production, from the chassis to the suspension to the English ash wooden frame. It’s a testament not just to the Morgan car but to those who invest their time, skill, and livelihood into its heritage.

Synopsis

Making a Morgan is divided into two sections: “The Morgan Story” and “Making a Morgan.”

The first portion, 50 pages titled “The Morgan Story,” chronicles the company’s formation and early years, even back to the Morgan family’s beginnings in 1534. This detailed history is filled with familial anecdotes, rare insights, and Morgan family photos. But, it’s not just a genealogy; readers will quickly notice the principles of the company throughout its history–the belief that making a product is about love, not money.

The second half, “Making a Morgan,” plays out like a journal or narrated television documentary. The authors spend 17 work days (May 4-26, 2015) witnessing the construction of a Morgan Plus 4 by the hands of lifelong master craftsmen. From the first order to heading for dealership delivery, the journey of a car within this secretive factory is narrated and photographed in a way you can envision as you read. Profiles on craftsmen are included, whose work is tied to the brand’s family-run legacy.

A quote from the prologue sums the book up nicely: “Whether or not the reader possesses a Morgan, or if, after reading this book, you might consider purchasing one, or if you would simply like to be present at the creation of one of these fascinating automobiles—we invite you, via this book, to experience a unique and exceedingly vibrant piece of automotive history.”

Product Quality

The front of Making a Morgan is simply gorgeous. The choice and placement of the finished Morgan on the cover is eye-catching and contrasts perfectly to its visually textured background. The book’s cover is very sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity, though, so it behooves the reader to take extra care so it doesn’t warp like our copy began to.

Inside, the book contains 160 sturdy pages with around 380 crisp images showing details of the car’s creation. Sections are divided into short six-page entries, with each page containing 33% text and 67% photographs. The text is spread out into 2-to-3-sentence paragraphs that are easy to skim and don’t look congested (like most coffee table books). The sentences are short, conveying the intent and important ideas in a casual tone.

The pictures even contain captions that reiterate what’s going on in them, for those of us who don’t know much about manufacturing.

Overall Review

From my perspective, this is probably the best testament to the Morgan you can find in book form. It provides both a large context to the company and a chronicle of the minute details of the cars. Together, those aspects capture the spirit of what makes Morgans special. You can sense the respectful attitude in the tone, a perspective that is imparted to the reader rather than forced on.

Making a Morgan is written by observant, thoughtful authors who deftly make the subject matter comprehensible to the reader. Seeing hand-built production of the classically-styled Morgan documented in such detail is humbling. We can all learn from it–driving isn’t just about selling cars to make money; it’s about the joy of driving. That’s what makes the Morgan–and this book–a work of art.

The price of the book is high for anyone unfamiliar with the brand, but it’s a must-have for Morgan fans (who should have pre-ordered their copies by now). Still, even if a naive reader like me who didn’t know anything about the Morgan Company can appreciate this testament to the brand, surely anyone can.

Making a Morgan: 17 Days of Craftsmanship:

Step-by-Step from Specification Sheet to Finished Car

Written and Photographed by Andreas Hensing & Dagmar Hensing

Product Details: Hardcover, 160 pages, 11.5 x 9.8 inches

Price: $75.00 / £40.00 (plus applicable postage fees)

Publication Date: October 2015

ISBN: 978-1-845848-73-6